Cassavetes -Rowlands: a life well worth a movie

About one of the most important collaborations of the New American Cinema

To my English speaking readers: since my native language is Spanish, I apologise in advanced for any mistakes that you can find in the English version of this post. Thanks for your support! 😊

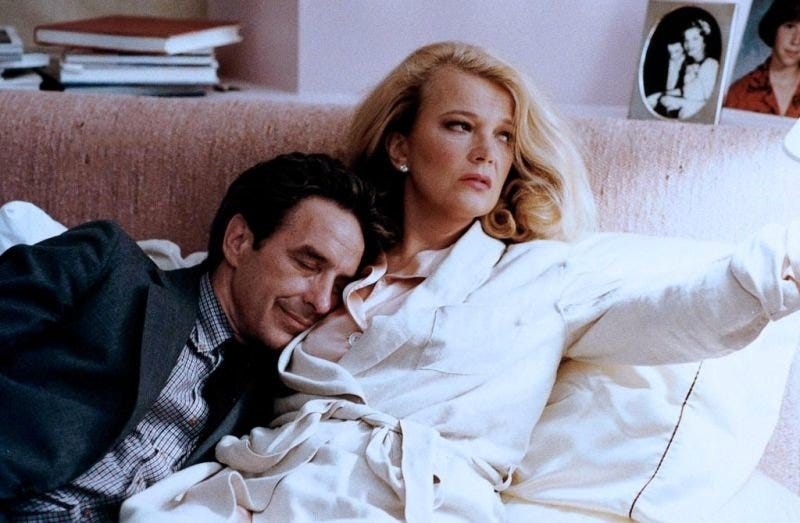

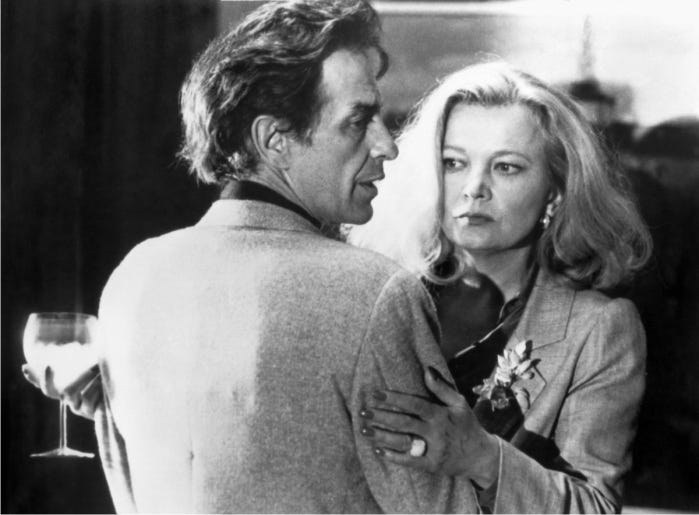

In one of the very few times Gena Rowlands has agreed to discuss her work with her late husband, John Cassavetes, the reporter asked if she ever revisited the films they made together. She said she never does, she doesn’t need to, she can just close her eyes and watch those movies, frame by frame, inside her head. They made seven films together (A Child is Waiting, Faces, Minnie & Moskowitz, Opening Night, Gloria, A Woman Under the Influence and Love Streams). The last one was recorded in 1984.

They met in New York, when both studied acting in the AADA (American Academy of Dramatic Arts) in the early 50s. John Cassavetes, a true New Yorker, had already became notorious for being a complicated man searching for trouble. Gena Rowlands, who came from a very stable and comfortable upbringing, was pure sophistication.

They were opposites, yet they fit in with each other. Cassavetes said that the first time he saw her he knew he would marry her. They tied the knot in 1954.

That was the beginning of an artistic collaboration that would last the same as their marriage, until 1988, when Cassavetes died from cirrhosis, at the age of 59. A collaboration that was key in the making of the New American Cinema.

Despite being a huge fan of Capra’s happy endings, Cassavetes was also strongly influenced by Italian neorealism, Godard, Kurosawa, Bergman and Dreyer (as he acknowledges in Ray Carney’s book Cassavetes on Cassavetes). And, somehow, Capra’s optimistic representation of the American way of living is perfectly mixed with European’s avant-garde cinema in Cassavetes’ movies, which made him the trailblazer of American independent cinema.

With these influences in mind, the Rowlands-Cassavetes duo started to turn their life together in cinema. He had already tried directing other people’s projects, but those experiences where rare and disappointing. There’s a rumour that it even got violent between him and Stanley Kramer during the editing of A Child is Waiting. Cassavetes understood, quite early in his career, that if he was to make cinema it had to be with his own rules.

So, they decided that both himself and Rowlands would work as actors and use that money to make their own films together (she was already a well known actress, with many projects in film and television). They built their small world that rolled around cinema. Cassavetes would write and direct his own stories, with a really small budget, and worked with a recurrent small crew, led by Rowlands, Peter Falk, Ben Gazzara and Seymour Cassel.

They softened the lines between real life and fiction. Cassavetes would often push his actors to the edge, and he and Rowlands sometimes brought the fight from home. Their house was also their workplace, where they edited the films. The scenes he used to write, full of witty dialogues, mirrored the legendary barbecues they used to host, with the attendance of the exact same cast.

They were also in charge of finding distribution for their films, and even visited cinemas where movies they liked were shown and ask them to take their project. They would go out in the streets and hang posters anywhere in the middle of the night. Cinema was their life.

Though admired by many, their movies were not people pleasers. They were long, full of dialogue, with unstable characters and sometimes intentionally uncomfortable. A Woman Under the Influence, Gloria and Opening Night are incredible portraits of emotional instability and the fear of getting old.

Cassavetes, who often blamed himself for dedicating more attention to his movies than to his personal life, made up for it by giving Gena Rowlands some of the most interesting female roles ever seen on screen. And she responded with some of the best performances, for their complexity, in the history of cinema.

In 1984 the couple made what would be their last film together, Love Streams. The male role was originally written for John Voight and, when he couldn’t make it, Cassavetes stood up and took the role himself. This is how a movie about relationships, with certain autobiographical touches, became the last gift from Cassavetes to Rowlands and their last project together.

It’s taken decades for the industry to reclaim both Cassavetes’ work and Rowland’s part in it. From his first movie, Shadows, to Faces, Opening Night, Minnie & Moskowitz (his peculiar take on romantic comedies) or The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, Cassavetes’ movies have become some of the main references for American independent cinema.

The director died in 1988, but Rowlands kept the same commitment to the work they made together: she’s barely given any interviews, she’s reluctant to talk about their life together and she doesn’t discuss their creative process. For decades, she’s remain custodian of their legacy, keeping fiercely the keys of a life well worth a movie.